![]()

British 6th Airborne Division

In 1940 the British established the Central Landing School at Manchester's Ringway airport to evaluate airborne operations under the aegis of the Director of Combined Operations, but this effort enjoyed only a low priority until Prime Minister Winston Churchill minuted the Chiefs-of-Staff Committee that he wanted to see the creation of a 5,000-man parachute corps without delay. Volunteers of the right calibre were found without difficulty, and progress was made in the development of airborne units and tactics, but the limiting factor was the Royal Air Force's lack of adequate transport and glider-towing aircraft, together with this service's reluctance to see any of its strength diverted to a secondary task, as the RAF saw such operations.

The UK's first operational airborne unit was No. 2 Commando, which became the 11th Special Air Service Battalion (with one parachute wing and one glider wing) during November 1940 and during September 1941 the 1st Battalion, The Parachute Regiment, when it became the first unit to be absorbed into Brigadier R.N. Gale's newly created 1st Parachute Brigade.

Two more battalions were soon raised, and in October 1941 Major General F.A.M. Browning was appointed to the new position of Commander, Para-Troops and Airborne Troops. At the same time, an infantry brigade was diverted to become a gliderborne air-landing brigade. By the end of 1941 it was clear the british airborne warfare capabilities merited ew organization, the more so as the Americans had promised large numbers of Douglas C-47 Skytrain transport and glider-towing aircraft that entered British service with the name Dakota. In November of that year Browning was appointed to command of the British 1st Airborne Division.

The formation entrusted with the airborne assault on the left flank of the British assault landing in Operation Overlord was the British 6th Airborne Division commanded by Major General R.N. Gale, who led the division from its creation to 8 December 1944, when he was succeeded by Major General E.L. Bols. The task of the division in Operation Overlord was to land units by parachute and glider in the area to the east of the seaborne landings for the establishment of an air-head whose two primary tasks were the capture of the Canal de Caen and River Orne crossings midway between Caen and Ouistreham, and the provision of a left-flank guard for the seaborne landings against German attacks from the east.

The British 6th Airborne Division had been created on 3 May 1943 with the formation of the divisional headquarters, but the divisional commander assumed command only four days later, and the divisional headquarters was brought up to full establishment only on 23 September 1943. The division's first element was the 6th Airlanding Brigade, which came under command on 6 May 1943, and this was joined later in the same month by the 3rd Parachute Brigade and the 72nd Independent Infantry Brigade, which arrived on 15 and 28 May respectively.

The latter unit remained part of the division for only three days to the end of the month, and was supplanted on 1 June 1943 by the 5th Parachute Brigade, whose HQ was created out of that of the 72nd Independent Infantry Brigade. For the rest of the war the British 6th Airborne Division's units were the 3rd and 5th Parachute Brigades and 6th Airlanding Brigade.

The British 6th Airborne Division served under the GHQ Home Forces from its creation to 3 December 1943, when it passed to control of the HO Airborne Troops for the period between 4 December 1943 and 5 June 1944. From the next day the British 6th Airborne Division came under the British I Corps for the Normandy campaign, and remained under control of this formation until 30 August 1944, when it passed to the control of the British 21st Army Group before returning to the UK on 3 September 1944 as a part of the British I Airborne Corps from 5 September 1944. Command passed to the War Office on 12 September and then back to the British I Airborne Corps on 1 October 1944.

The division returned to North-West Europe on 24 December 1944 under command successively of the British 21st Army Group, British XXX Corps, 21st Army Group, British VIII Corps and finally 21st Army Group. The division saw no action during this period, and returned to the UK and control of the British I Airborne Corps on 24 February 1945. On 19 March 1945 the division was allocated to the US XVIII Airborne Corps, and fought under its command in the first stage of the Rhine battle (23 March — 1 April 1945) before coming under command of the British VIII Corps on 29 March 1945. The division saw no more fighting after the Rhine battle, but reverted to the US XVIII Airborne Corps on 1 May 1945. The division saw out the remaining days of World War II under US control, and reverted to the British I Airborne Corps only on 19 May 1945, when it returned to the UK.

At this point it is illuminating to consider the standard organization of the British airborne division at the time of Operation Overlord. The organization was based on a personnel strength of 12,148 all ranks, 6,210 vehicles together with 935 trailers, and weapons that ranged in size from pistols to cruiser tanks. The division's vehicles included 3,269 bicycles (1,907 MKV and 1,362 folding bicycles), 1,233 motorcycles (529 lightweight and 704 solo motorcycles), 1,044 cars (904 5-cwt Jeeps, 115 miscellaneous cars and 25 scout cars), 25 Universal on Bren Carriers, 24 ambulances, 1201 5-cwt trucks, 438 3-ton trucks, 26 tractors, and 22 tanks (11 cruiser and 11 light tanks).

The weapons included 2,942 pistols, 7,171 Lee Enfield rifles, 6,504 Sten submachine guns, 966 Bren light machine guns, 46 Vickers Mk I medium/heavy machine guns, 535 mortars (474 2-in, 563-in and 54.2-in weapons), 392 PIAT anti-tank weapons, 23 20mm towed anti-aircraft guns, 38 man-portable flame-throwers, and 127 guns (27 75mm towed pack howitzers, 84 towed 6-pounder anti-tank guns and 16 towed 17-pounder anti-tank guns).

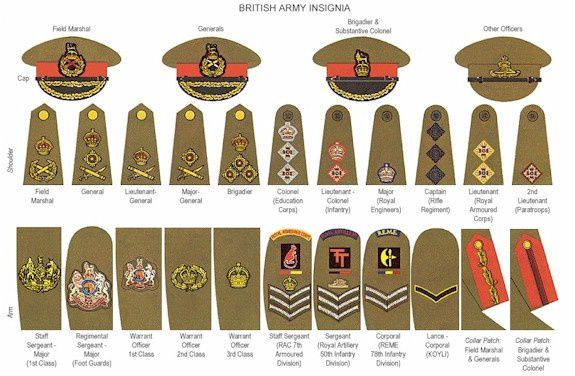

Divisional command was exercised from the Divisional HQ, where the divisional commander and his staff enjoyed the support of several types of specialist as well as the Airborne Divisional HQ Defence Platoon, the Divisional Field.

Security Section and an independent parachute company. The Divisional HQ controlled the formation's three brigades (two parachute and one airlanding) and the organic divisional troops. Each brigade was based on a Brigade HQ with its own Brigade HQ Defence Platoon and three battalions. The three battalions were the fighting strength of the brigade: In the parachute brigades, each battalion had a strength of 29 officers and 584 other ranks in one HQ company and three rifle companies.

The HQ company had five platoons, two of them each equipped with four 3-in mortars and one with 10 PIATs. Each rifle company had three platoons. In the glider-borne airlanding brigade, each battalion had a strength of 47 officers and 817 other ranks in one support company, one anti-aircraft/anti-tank company and four rifle companies.

The support company had six platoons including one with four 3-in mortars. The anti-aircraft/anti-tank company had four platoons including two with 12 20mm AA guns and the other two with eight 6-pounder anti-tank guns. Each rifle company had four platoons. It should also be noted that the gliders used for the delivery of the airlanding brigade were operated by wings whose varying number of squadrons each had a varying number of flights each with 20 gliders. Each glider was flown by two men of The Glider Pilot Regiment, who were trained to fight alongside the men of the airlanding brigade.

The capability of the parachute and airlanding brigades was greatly bolstered by the divisional troops controlled by Divisional HQ. The Royal Armoured Corps provided an airborne armoured reconnaissance regiment. The Royal Artillery provided an HQ Airborne Division RA controlling one airlanding light regiment and one airlanding anti-tank regiment. The Royal Engineers provided a HQ Airborne Division RE controlling two parachute engineer squadrons and one airborne field company.

The Royal Signals provided an Airborne Divisional Signals unit. The Royal Army Service Corps provided an HQ Airborne Division RASC controlling one airborne light company and two airborne light divisional companies. The Royal Army Medical Corps provided two parachute field ambulances and one airlanding field ambulance. The Royal Army Ordnance Corps provided one airborne divisional ordnance field park.

The Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers provided an HQ Airborne Division REME controlling one airborne divisional workshop, one armoured Airlanding Light Aid Detachment ‘Type A', one unarmoured Airlanding Light Aid Detachment ‘Type A', four Airlanding Light Aid Detachments ‘Type B' and one Airlanding Light Aid Detachment ‘Type C'. And the Corps of Military Police provided an airborne divisional provost company. The organic troops were completed by an airborne divisional postal unit, a mobile photo enlargement centre and a forward observer unit.

Major General Richard ‘Windy' Gale was a pioneer of British airborne forces, and raised the 1st Parachute Brigade. By 1944 he had risen to command of the British 6th Airborne Division, which he led under very difficult circumstances in Operation Overlord. Though superficially a typical Indian Army officer (he had been born in India and was Master of the Delhi Foxhouds before World War II), Gale was in fact a daring planner who could cause concern by the blunt lucidity of his words but who proved himself capable of infusing his men with the confidence and skills to carry out his plans.

![]()

At dawn on the 6th June 1944, two Allied armies, one British and one American, landed on the beaches of Normandy in France. It was the largest invasion ever attempted, and its ultimate goal was to secure a foothold in Europe, to defeat Germany and liberate the Continent from Nazi rule. Leading the invasion, landing by parachute and glider, several hours before the first troops assaulted the beaches, were three Airborne Divisions; two were American and landed in the west, the other, the 6th British Airborne Division, landed in the extreme east.

The main tasks of the 6th Airborne Division were as follows:

1. To capture the Bénouville and Ranville Bridges.These strategically vital bridges, if held against counterattack, would not only prevent the Germans from moving decisively against the flank of the British and Canadian seaborne troops as they advanced inland,but they would also enable the Allies to advance eastwards.

2. The destruction of the Merville Battery. Several miles to the north-east of these bridges was an imposing fortification that contained four large calibre guns, which could do terrific damage to the invasion fleet. The 6th Airborne Division had to attack and destroy these guns in the hours before the landings took place.

The first British troops that arrived in France were the one hundred and eighty men of Major John Howard's "coup de main" force, consisting of two platoons of "B" and all of "D" Company of the 2nd Oxford & Bucks Light Infantry. Travelling in six gliders, they landed within yards of both the Bénouville and Ranville Bridges, and within ten minutes they had brilliantly captured both of them intact. Bénouville Bridge would later become more famously known as Pegasus Bridge.

Several miles to the east, the four thousand paratroopers of the 3rd and 5th Parachute Brigades were not so lucky. Poor weather conditions and high winds obscured the drop zone and scattered the parachutists as they jumped. Many men dropped miles from where they should have been, others drowned in ground that had been flooded by the Germans. Gradually the six battalions of these two brigades formed up at their rendezvous points, however they could only muster between 25 and 60% of their full strength.

Despite this, they went about their tasks. The 7th Parachute Battalion relieved Howard's men at the Bridges, the 12th and 13th Parachute Battalions secured several villages to the south-east to shield the Bridges against attack from the east of the River Orne, whilst the engineers of the 3rd Parachute Squadron, supported by the 8th and 1st Canadian Parachute Battalions destroyed five bridges across the River Dives, eight miles to the east, thus greatly impeding subsequent German counterattacks.

Of all of these units, the 9th Parachute Battalion suffered worst from its drop. Their task was to destroy the Merville Battery, but after hours of waiting at the rendezvous no more than one hundred and fifty of their men had arrived, and very little of their specialist assault equipment had been found. Their commander, Lt-Colonel Terence Otway, was left with no choice but to attack with what he had.

The Battery was a formidable position. It was defended by one hundred and thirty Germans, supported by numerous machine-gun positions, all sitting inside two huge belts of barbed wire, in between which was a minefield. Silently, the paratroopers cut their way through the wire and cleared paths of mines. As they were forming up for the attack, they were spotted and fired on by no fewer than six machine-guns. As these were being dealt with, Otway gave the order to attack, whereupon the assault party charged across the minefield, lobbing grenades and firing from the hip at any sign of enemy resistance.

The Germans fought back hard and cost the assault party dear, however they could not be prevented from reaching the casemates, and once inside they engaged their defenders hand to hand. At a heavy cost, the guns were destroyed and in so doing the lives of hundreds, possibly thousands of men in the invasion fleet had been saved. Of the one hundred and fifty paratroopers who had attacked the Merville Battery, sixty-five were either killed or wounded, whilst of the one hundred and thirty strong German garrison, only six escaped injury.

By dawn, the 6th Airborne Division was holding a firm defensive position as the Allies began to land on the beaches. The assault began with a terrific bombardment of the beach defences by bombers and warships, after several hours of which the assault infantry pressed forward in their landing craft. By the end of the day, all of the beaches had been captured and the Allies were edging ashore in spite of heavy casualties, the worst of which had been suffered by the Americans on Omaha Beach.

On Sword Beach, nearest to the 6th Airborne Division, the Commandos of the 1st Special Service Brigade arrived, and with great speed they cut their way through German resistance to link up with the Airborne troops. The Commandos, having crossed the bridges, pushed on northwards to the aid of the desperately weak 9th Parachute Battalion. Elsewhere, the fiercest fighting was experienced by the 12th Parachute Battalion, who fought off two heavy attacks on their positions, and in particular by the 7th Parachute Battalion, who had only a third of their strength and were struggling to hold the western end of Pegasus Bridge from determined German attacks. Despite heavy casualties, they yielded no ground and by midnight they were relieved by the main force of infantry arriving from Sword Beach.

Throughout the next week the 6th Airborne Division held its bridgehead across the River Orne against increasingly vicious attacks. Time after time they threw these back with severe casualties, however a steady toll was being taken on their own numbers and as such it was proving difficult for them to hold such a wide expanse of territory. Gradually the attacks became focused upon a crucial wide ridge, which overlooked the British invasion area and therefore it was vital that this ground be held.

Here, the well-equipped German 346th Division made numerous attempts to gain a foothold by constantly attacking the 1st Canadian and 9th Parachute Battalions as well as the 1st Special Service Brigade. On the 12th June, a particularly heavy attack was successfully beaten off, however the position of the two parachute battalions was precarious and it was doubtful whether they could withstand another attack of such magnitude.

The main position from which the 346th Division was fighting was the village of Bréville, which was sited upon the ridge and also served as a potentially destabilising wedge between the positions of the Paratroopers and the Commandos. The commander of the 6th Airborne Division, Major-General Richard Gale, decided that Bréville had to be captured immediately or else his defence might fold. During the night of the 12th June, the 12th Parachute Battalion attacked and successfully captured the village, though at a very high cost. The British lost one hundred and sixty two killed to the Germans seventy seven.

Despite this, The Battle of Bréville was a crucial victory because it truly secured the 6th Airborne Division's position, and with it the entire Allied left flank. Furthermore, the offensive spin of the 346th Division had been shattered, and from the 12th June onwards, no further serious attacks were mounted against the 6th Airborne Division.

For the following two months, the Division fought a static defence. That is to say they remained firmly in their positions and made no attempts to advance, but at the same time they sent out numerous heavy patrols, by day and night, to seek out and raid any enemy in their area. The purpose of this strategy was to destabilise the Germans and so prevent them from becoming comfortable enough to contemplate another offensive against the Division. The Airborne troops, and in particular the Commandos, were ideally suited to this task they did an excellent job of unsettling and frustrating their opponents.

Elsewhere, the Allied armies were advancing slowly in the face of stiff opposition. However the Germans were gradually worn down and, in late July, the Americans succeeded in breaking through the lines of the German Seventh Army and began to encircle them in what was to become known as the Falaise Pocket. Inevitably, the Germans were heavily defeated in Falaise, and with their front line in disarray they fell back, rapidly pursued by the Allies. Within weeks, most of France and Belgium had been liberated.

The 6th Airborne Division took part in this advance despite the fact that many doubted that they would be able to maintain the pace, because they had far fewer vehicles and support equipment than a standard British infantry formation had available to it. Confounding the skeptics, the Division, through quick marches and intelligent use of what resources they had, were not in the slightest hindered in this regard and in just ten days they waged a fighting advance over a distance of some thirty miles.

Throughout this time, the Germans fought a stubborn rearguard action, particularly across the three rivers that the Division had to ford, but nevertheless they overcame all that was before them, and on the 27th August the Division was ordered to halt at the mouth of the River Seine. Their role in the Normandy campaign was at an end and in early September they returned to England.

Throughout the three months of fighting in Normandy, the 6th Airborne Division had made a crucial contribution to the success of the invasion. All of their objectives had been achieved during the first few hours of the landing, and over the coming days they gave no ground whatsoever in the face of determined German counterattacks.

Their casualties, however, had been considerable. Of the approximate ten thousand men of the Division, one thousand one hundred and forty-seven had been killed, two thousand seven hundred and five were wounded, and nine hundred and twenty-seven were missing. The fact that, in spite of this loss, mostly as a consequence of the scattered drop on the first night of the landings, the Division still manage to accomplish its tasks and hold such a wide expanse of territory, can only be attributed to the high calibre of its soldiers.

![]()

![]()

Dakota -C-47

Airspeed Horsa Invasion Glider

![]()

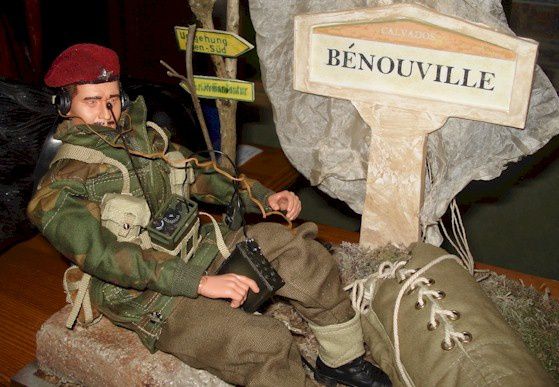

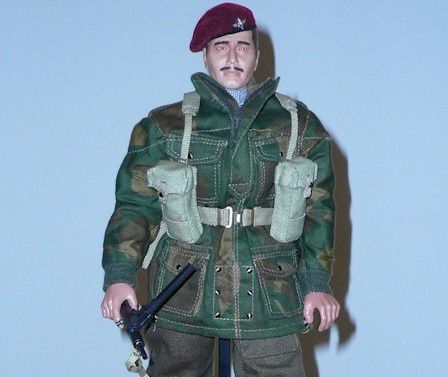

|

Sergeant UK Airborne, 1944 |

![]()

![]()

|

|

STEN Mk.II (2) |

STEN Mk.III (3) |

STEN Mk.V (5) |

|

Caliber |

9x19mm |

9x19mm |

9x19mm |

|

Weight, empty |

3,26 kg |

3,18 kg |

3,86 kg |

|

Length |

895 mm |

762 mm |

762 mm |

|

Barrel length |

196 mm |

196 mm |

196 mm |

|

Rate of fire |

550 rounds per minute |

550 rounds per minute |

600 rounds per minute |

|

Magazine capacity |

32 rounds |

32 rounds |

32 rounds |

|

Effective range |

150-200 meters |

150-200 meters |

150-200 meters |

The STEN name came out of names of the designers (R. V. Shepard and H. J. Turpin) and from the factory where they worked (Enfield arsenal). It was one of the most crude and ugly and simply, but effective submachine guns of the WW2. Almost 4 millions of STEN guns of different versions were made between 1941 and 1945. STEN guns were made not only in Royal Small Arms factory in Enfield; other makers included famous British gunmaking company of the time BSA Ltd, as well as Royal Ordnance Arsenal in Fazakerly, England, and Long Branch Arsenal in Canada.

The first STEN, STEN Mk.I (full official name was 9mm STEN Machine Carbine, Mark 1), was developed in mid-1941. It was blowback operated, automatic weapon that fired from the open bolt. Trigger unit permitted for sigle shots and full automatic fire, controlled by the cross-bolt type button, located in front and above trigger. The tubular receiver and the barrel shroud were made from rolled steel. The gun was fed from left side mounted box magazines. The stock was of skeleton type, made from steel. Sights were fixed, pre-adjusted for 100 yards distance, peep hole rear and blade front. The Mk.1 featured spoon-like muzzle compensator. Some guns featured small folding forward grip. Total production of Mark 1 and slightly modified Mark 1* STEN machine guns was about 100 000.

The STEN Mk.II submachine gun was most widely made gun in entire STEN series, with about 2 millions of Mark 2 being made during the war. It was slightly smaller and lighter than Mk.I. Basic design was the same as Mark 1, with omission of all wooden parts of Mk.I and shorter barrel jacket, which made the Mk.II lighter than its predecessor. Magazine housing could be rotated for about 90 degrees down to close feed and ejection apertures during transportation and off-battle carry (this feature caused much troubles as the rotary unit was not very durable and magazine could be misaligned during combat, what led to feed malfunctions and jams). Another source of problems was magazine spring, so magazines were routinely loaded with 28-30 rounds instead of "full capacity" 32 rounds to reduce strain on the magazine spring.

Some Mk.II STEN guns were manufactured with integral silencers for undercover operations and were marked as Mk.II(S). These guns had shortened barrels enclosed into integral silencer. The silencer was rather effective so most audible sound when firing Mk.IIS was the clattering of the bolt moving back and forth in the receiver. Contemporary manuals advised that Mk.IIS submachine gun was to be fired in semi-automatic mode; the ful-automatic fire was reserved for emergency situations, as it decreased the service life of silencer significantly.

The STEN Mk.III was modification of Mk.I. The major change was that the receiver and the barrel shroud were made from single tube (wrapped from sheet-steel and welded at the top) that extended almost to the muzzle. Another changes included fixed magazine housing for improved reliability and small finger guard in the front of the ejection port. Internally, Mk.III was similar to Mk.I and has same variety of skeleton stocks. Mk.III first appeared in 1943.

The STEN Mk.IV was made in experimental form only, and did not entered the production. It was originally intended for airborne troops.

The STEN Mk.V submachine gun was an attempt to made Mk.II a more "good looking'" gun. Being internally the same as Mk.II, the "STEN Mk.V machine carbine" featured wooden buttstock and rear pistol grip, new front sight and bayonet mount. Early Mk.V's also featured wooden front grips, but these were prone to breakage and thus were removed soon. STEN Mk.V appeared in 1944 and remained in service until the early 1960s', and then replaced by Sterling submachine guns.

The Lee-Enfield was, in various marks and models, the British Army's standard bolt-action, magazine-fed, repeating rifle for over 60 years from (officially) 1895 until 1957, although it remained in British service well into the early 1960s and is still found in service in the armed forces of some Commonwealth nations. In its many versions, it was the standard army service rifle for the first half of the 20th century, and was adopted by Britain's colonies and Commonwealth allies, including India, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada.

Rifle No 4 Mk I Cal 303*

By the late 1930s the need for new rifles grew, and the Rifle, No. 4 Mk I was first issued in 1939 but not officially adopted intil 1941. The No. 4 action was similar to the Mk VI but lighter, stronger, and most importantly, easier to mass-produce. Unlike the SMLE, the No 4 Lee-Enfield barrel protruded from the end of the forestock.

The No. 4 rifle was considerably heavier than the No. 1 Mk. III, largely due to its heavier barrel, and a new bayonet was designed to go with the rifle- a spike bayonet (which was essentially a steel rod with a sharp point), and was nicknamed "pigsticker" by soldiers. Towards the end of WWII, a bladed bayonet was developed and issued for the No 4 rifle, using the same mount as the spike bayonet.

During the course of World War II, the No. 4 rifle was further simplified for mass-production with the creation of the No. 4 Mk I* in 1942which saw the bolt release catch removed in favour of a more simplified notch on the bolt track of rifle's receiver. It was produced only in North America, with Long Branch Arsenal in Canada and Savage-Stevens Firearms in the USA producing the No. 4 Mk I* rifle from their respective factories. On the other hand, the No.4 Mk I rifle was primarily produced in the United Kingdom.

| Lee-Enfield Mk .1 |

No.4 Mk.1 |

|

Caliber |

.303 British (7.7x56mm R) |

|

Action |

manually operated, rotating bolt |

|

Overall length |

1132 mm |

|

Barrel length |

640 mm |

|

Weight |

3.96 kg |

|

Magazine capacity |

10 rounds in detachable box magazine |

![]()

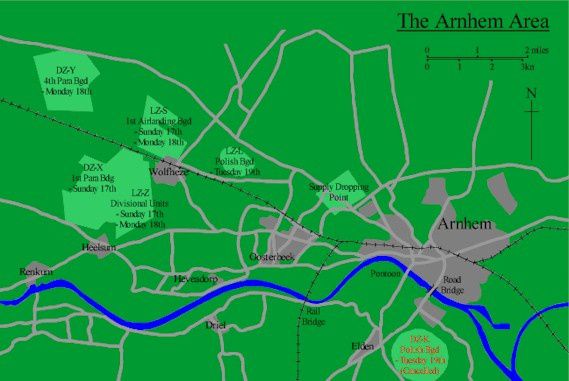

1st Airborne Division

Operation Market Garden

(September 17, 1944–September 25, 1944)

NETHERLANDS

Survivors From Hell

British / Polish landings in Arnhem

CANADA

Paratroopers of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion preparing for a patrol.

January 15, 1945, Bande, Belgium.

MEMORIAL

/idata%2F0396584%2FKOREA%2F71910_korea_MIA1_800.JPG)

/idata%2F0396584%2FU.S.ARMY-POST-WW2%2Fphot4901a.jpg)

/idata%2F0396584%2FDRAWINGS-UNIFORMS-WW2%2F30-451-09b-2.jpg)

/idata%2F0396584%2FP-40%2F44FS000.jpg)

/idata%2F0396584%2FGERMAN-U-BOAT%2FBundesarchiv_Bild_101II-MW-1031-28-_Lorient-_U-31.jpg)

/idata%2F0396584%2FSOVIET-ARMY-WW2%2F1.jpg)